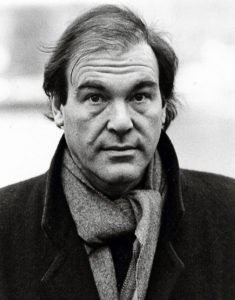

Acclaimed screenwriter and director Oliver Stone, whose work includes “Wall Street” (1987), “The Doors” (1991), “JFK” (1991) and “Nixon” (1995), served in the Army and deployed to Vietnam from 1967 to 1968. His wartime experiences would shape some of his later films.

Stone enlisted in April 1967. He requested combat duty and that’s exactly what he got. He arrived in South Vietnam Sept. 16, 1967, assigned to 2nd Platoon, Bravo Company, 3rd Battalion, 25th Infantry, stationed near the Cambodian border.

He was wounded twice in combat and was awarded the Bronze Star Medal for valor. His wounds were either a bullet or shrapnel to the neck and the other was shrapnel to the legs and buttocks.

Regarding the Bronze Star, Stone wrote about it in his rather long-titled book: “Chasing the Light: Writing, Directing, and Surviving Platoon, Midnight Express, Scarface, Salvador, and the Movie Game.”

“We had run into a mean little ambush which had cost us a lieutenant and a sergeant, as well as our scout dog, a German shepherd I’d taken a liking to. It was one of those strange firefights that grew from a few random shots into a disorganized raging storm of bullets,” he wrote.

“Maybe I was just cold and angry about the dog’s death or the futility of it all. Or maybe I just had a headache, and the sun was burning too hot in my eyes. … All I knew was that this was my moment to act,” he said.

“Exposing myself to the enemy, I moved up quickly on a one-man spider hole between our two platoons — from which I sensed someone had just fired. On instinct, from 15 yards out, I pulled the pin on my grenade and hurled it. It was a crazy risk. If I’d overthrown the grenade, it probably would’ve wounded or killed some of our own men crouched beyond the hole.”

“But it was a perfect pitch, and the grenade sailed into the tiny hole like a long throw from an outfielder into a catcher’s mitt, followed quickly by the concussed thump of the explosion. Wow. I’d done it!” he said.

After recovering from his wounds, he transferred to the 1st Cavalry Division and was assigned to a long-range reconnaissance platoon.

On Jan. 1, 1968, Stone’s platoon, part of two battalions, was patrolling along the Cambodian border. That night, they came under a massive attack from a North Vietnamese regiment which outnumbered them.

The battle would last ‘till nearly dawn. “The sound of small-arms fire, heavy artillery and bombs hardly let up all night, bigger than any fireworks I’d ever seen. Stunningly beautiful, in its way,” he wrote.

“And now there was an enormous roar, like I suppose the end of the world sounds. Like a shark cutting through water, an F-4 Phantom jet fighter was coming in very low over our perimeter out of the night sky. So low, that doomsday sound. They were going to drop their payload on us and we were all going to die.”

“I jumped into the closest foxhole and buried myself as deep as I could in the earth, which trembled and shook as a 500-pound bomb dropped somewhere close,” he recalled.

“Full daylight revealed charred bodies, dusty napalm and gray trees. Men who died grimacing, in frozen positions, some of them still standing or kneeling in rigor mortis, white chemical death on their faces. Dead, so dead. Some covered in white ash, some burned black. Their expressions, if they could be seen, were overtaken with anguish and horror.”

“In the next hours I grasped the extent of what had happened. Most of the dead were fully uniformed, well-armed North Vietnamese regulars. Those who were relatively intact we brought in on stretchers, walking out to find them, or pieces of them. A bulldozer had been airlifted in to dig burial pits. I helped throw the bloating bodies into the giant pits late into that day.”

“There were maybe 400 of their dead. We’d lost some 25 men, with more than 150 wounded, yet I hadn’t fired a single shot or even seen one enemy soldier. It was bizarre,” he wrote.

“We worked in rotating shifts, two men, three men, swinging the corpses like a haul of fish from the sea. Later we poured fuel on them, and then the bulldozers rolled mounds of dirt over them, so they’d be forever extinct. I was too young to understand. No person should ever have to witness so much death,” he said.

Stone was honorably discharged in November 1968, the same month he arrived stateside from Vietnam.

The Vietnam GI Bill helped pay for his enrollment in New York University, where he studied filmmaking under Martin Scorsese.

He broke into Hollywood as a screenwriting notable, with his Oscar-winning screenplay for “Midnight Express” (1978). A string of other screenplays he wrote followed, including “Conan the Barbarian” (1982), “Scarface” (1983), and “Year of the Dragon” (1985).

Stone’s Vietnam experience can be seen in three films he wrote and directed: “Platoon” (1986), “Born on the Fourth of July” (1989), and “Heaven and Earth” (1993).

“Platoon” was always Stone’s story and he worked 10 years to get it on screen, said retired Marine Capt. Dale Dye, who played Army Capt. Harris, the commander of Company B. Dye, who was also the film’s technical advisor, was the only Vietnam combat veteran on the set beside Stone. He shared some of his thoughts on the filming.

“Oliver and I often had intimate and unspoken moments sparked by something we were staging or filming. I recall both of us having to walk away for a few minutes while we were filming the scene that involved interrogating some villagers. We had employed actual Vietnamese refugees that we’d found in the Philippines and being surrounded by extras shrieking and conversing in Vietnamese brought us both right back to Nam,” he said in a Dec. 29, 2021, interview with this journalist.

“Most people don’t know it, but the patrol scene that runs during the opening credits was actually the last day of my training for the cast. Oliver observed the patrol I was leading along a riverbed and loved the look of it, so he changed what he originally had planned and filmed the patrol instead,” Dye recalled.

“He was always doing things like that, shooting targets of opportunity, whenever he saw something that jogged his memories of his own experiences. And, it was really valuable to me personally as an aspiring filmmaker. I learned a ton just watching Oliver and Bob Richardson work,” he said. Richardson was the film’s cinematographer.