The Nuremberg Christmas market has more than 180 wooden booths with red and white roofs. The market is open until Dec. 24.

The City of Nuremberg is known for one of the oldest Christmas markets in Germany, called “Christkindlesmarkt,” and for the production of “Lebkuchen,” or gingerbread.

Historical documents mention a pre-Christmas shopping fair that took place in 1628 for the first time. In the 18th century, selling booths were set up. A listing from 1737 shows 140 names of local craftsmen taking part in that Christmas market. Toward the end of the 19th century, the Christmas market became less important, but after World War II it was revived.

Today it looks like a little town with more than 180 wooden booths with red and white roofs made of cloth.

The most traditional items available for sale are holiday decorations, arts and crafts, toys, the plum men and sweets, including fruit bread and gingerbread.

market.

Most visitors of the Nuremberg Christmas market will take the chance and buy “Nürnberger Lebkuchen,” the gingerbread, which is known all over the world.

In the 14th century, the making of gingerbread became popular in Munich, Frankfurt, Basel, Vienna and Nuremberg.

Beekeepers from a little town near Nuremberg helped bring fame and a good reputation to the town. With plenty of fir and pine trees, oak trees and linden, sloe trees, hazelnut bushes, spurge-laurels and heather growing in the forests near Nuremberg, enough nectar was available for the bees. The so-called “Zeidler,” forest and house beekeepers, founded a large guild, and harvested the honey from honeycombs in tree holes or crevices.

At that time, honey was the only existing sweetener. Due to worldwide commercial connections of local merchants, the bakers of gingerbread were able to receive all necessary ingredients — pepper, ginger, cinnamon and other spices.

In the Nuremberg area, the beekeepers maintained about 50 farms and in 1350, Emperor Karl IV gave them the privilege of being the only people authorized to harvest the honey in his forests. The beekeepers wore their own costumes, crossbow and arrows and were the emperor’s bodyguards. They also maintained their own court of justice where they handled all crimes committed in the forests and against the beehives.

In 1796, Prussian occupants limited this jurisdiction, and three years later, they took it away totally.

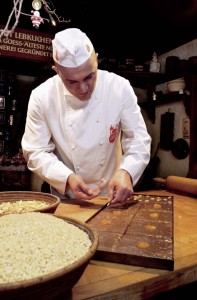

Today the making of gingerbread is still considered an art clothed in secrets. The modern production still relies on old recipes that masters have passed down from generation to generation. Gingerbread is a must when arranging a Christmas cookie plate in Germany.